Just 34 days before the end of World War II, a U.S. Navy cruiser was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine and sunk in the Philippine Sea.

The USS Indianapolis had been the ship of state of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and had just delivered core components of the Hiroshima-bound atomic bomb “Little Boy” off the coast of Japan four days earlier.

After unloading her top-secret cargo at Tinian and then making a quick stop in Guam to await further orders, the crew of the Indy were soon bound for the Philippine island of Leyte, unaware that their location had just been discovered by an enemy submarine.

A Japanese sonar man had picked up on the sound of rattling dishes in her kitchen from some 6 miles away. The submarine began stalking her through the water until it was close enough to engage.

The sub’s commanding officer, Mochitsura Hashimoto, gave the order to fire six torpedoes into her side at 12:04 a.m. on July 30, 1945. Two of the torpedoes hit their mark, and it took the Indy just 12 minutes to capsize and sink, forever entombing some 300 of her 1,195-man crew 18,044 feet beneath the surface of the moonlit water.

For the next five days, the nearly 900 sailors who had survived the sinking found their numbers whittled down as crew member after crew member fell victim to saltwater poisoning, drowning, delirium and shark attacks. Only 316 survived the horrific ordeal.

Survivor Harlan Twible later recounted his time in the water: “I saw some great heroism, and I saw some great fright, and I saw some things I wouldn’t ever want to talk about.”

When the survivors were first spotted on the fourth morning by 24-year-old U.S. search and reconnaissance air pilot Chuck Gwinn while he was looking for enemy vessels in the area, they had drifted apart from each other and were found in several groups across nearly 200 miles of ocean.

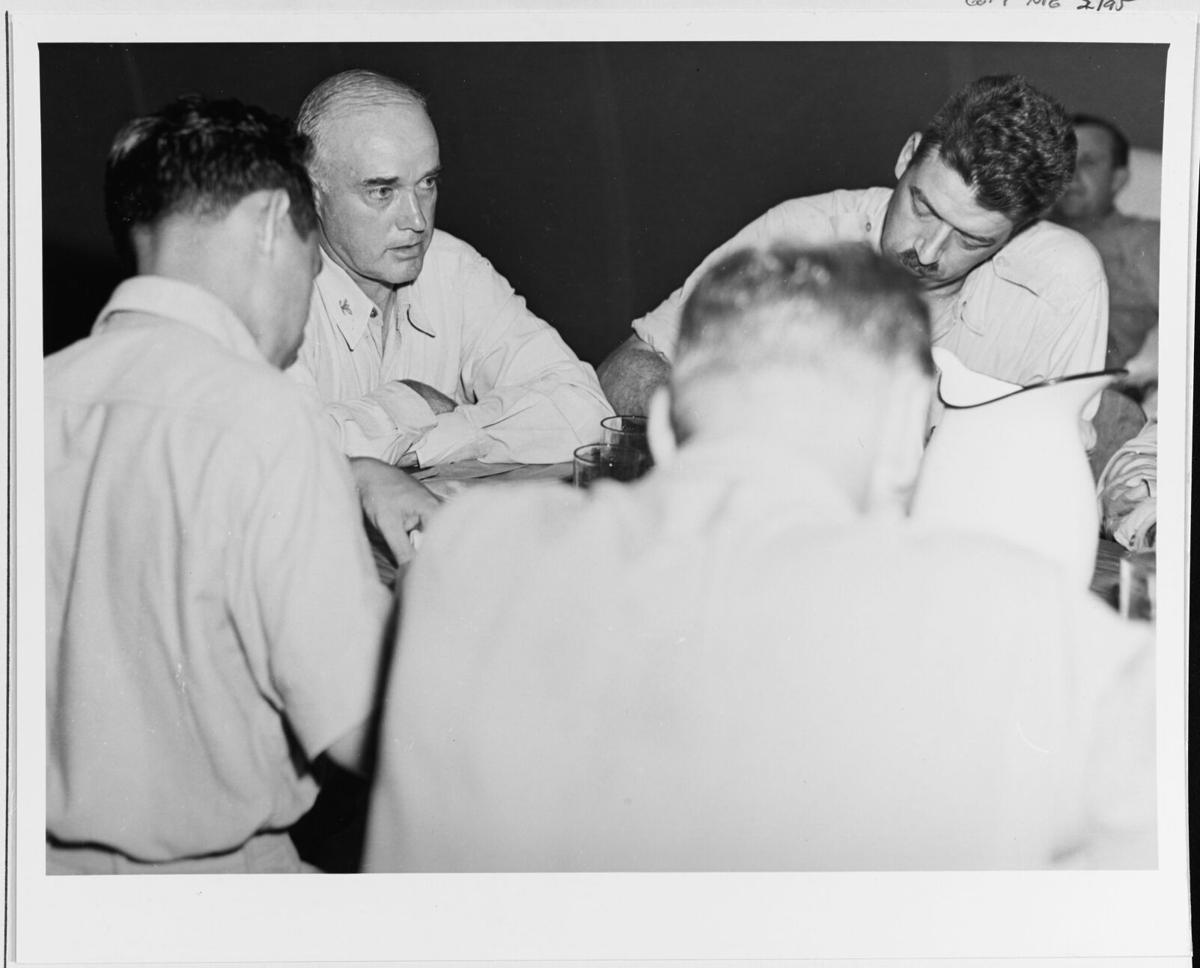

Their collective rescue took about 24 hours to complete – leaving some survivors in the water for five harrowing days. One of the discovered clusters of men contained the Indy’s captain, Charles McVay.

Despite the nightmare he’d just experienced and survived at sea, Capt. McVay soon found himself in a different kind of fight – this one with the United States Navy.

‘The Navy needed someone to blame’

The Navy had bungled many things regarding the Indianapolis and they knew it: They denied McVay the escort he’d requested for protection while traveling through enemy waters; they failed to respond to any of the distress signals sent from the Indy that listed its coordinates in the final moments of its sinking (the Navy has since disputed receiving any distress signals, though multiple servicemen claimed to have received them); they failed to recognize or report that the Indy had not arrived at Leyte when it was scheduled to; and they had provided McVay with an incomplete intelligence report in the first place – withholding the vital information they had come by through a top-secret code-breaking program that confirmed enemy submarine activity along the route the Indy would be taking to Leyte.

To prevent such blunders from getting out and possibly overshadowing the triumphant news of the likely ending of the war (the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima just two days after the survivors were rescued with “This one is for the Boys of the Indianapolis” written on its side), the Navy ordered a news blackout about the incident once the survivors were sequestered and convalescing on a nearby island.

In Washington, the Navy had already begun preparing for a court inquiry as requested by Adm. Chester Nimitz. Nimitz’s inquiry requested an investigation of the cause of the sinking, the culpability of any servicemen involved, and how the survivors had been discovered entirely by accident after the base at Leyte failed to report the ship as missing.

In the end, a few servicemen were reprimanded for their respective roles in not recognizing the Indy’s absence, but only McVay would be taken to trial and charged for the sinking of the ship once he arrived back on American soil.

The Navy all but spelled out their reasons for doing so in a letter their judge advocate general (JAG) sent officials at the time: “Full justification for ordering the trial … springs from the fact that this case is of vital interest not only to the families of those who lost their lives, but also to the public at large.”

In other words, “the Navy needed someone to blame for what The New York Times had already called ‘one of the darkest pages of our naval history,’” said Doug Stanton, author of “In Harm’s Way: The Sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis and the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors.”

Initially, Navy prosecutors tried to charge Capt. McVay with two counts of negligence: “failure to abandon ship in a timely manner” and “hazarding his ship” by failing to steer her in diagonal lines, a since-abandoned defensive maneuver known as zigzagging.

But the prosecutors soon realized they could not prove the first charge because the ship sank so quickly. So they put all their effort into making the second charge stick. McVay had already admitted that the Indy had not been zigzagging at the time of the attack, citing weather conditions. The Navy insisted on proving that his lack of doing so had been consequential.

Among the list of witnesses the prosecution called to testify against McVay was none other than the submarine commander who had sunk the Indy in the first place: Cmdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto. The decision caused an uproar among members of the press and politicians alike.

from JC’s Naval, Maritime and Military News https://ift.tt/2RBDv9z

via IFTTT

Leave a comment